Hello Everyone,

I have decided to write a series of blog posts that will coincide with my normal “what we’ve been up to” / “here’s something you may find interesting” sort of posts.

As the title suggests, this “Beekeeping Basics” series will focus on some basic fundamentals and understandings of beekeeping. I’m hoping that it will feed into any beginners’ course that you partake in or, as I know courses are quite hard to get onto after the initial April spate, this will aid you in your beekeeping journey until you can get on one. If you are enjoying these posts and are thinking about becoming a beekeeper yourself then, please see this post I wrote about how to do just that.

So, first things first, to get properly started in beekeeping we have to ask “what is a honeybee? And what is a colony made up of?”

In short, the honeybee is an 'eusocial' flying insect that relies on its unique ability to create stores from nectar and pollen, called honey, to survive the winter months. A colony is made up of three ‘castes’, the queen, worker bees, and drones. Each have their own roles in the hive and are necessary for the colony to thrive.

Eusocial: adjective of an animal species, (especially an insect) showing an advanced level of social organization, in which a single female or caste produces the offspring and non-reproductive individuals cooperate in caring for the young.

In Long, to truly understand a honeybee you need to look at the anatomy and the in-depth roles of each caste, which I’ll try to clearly outline below.

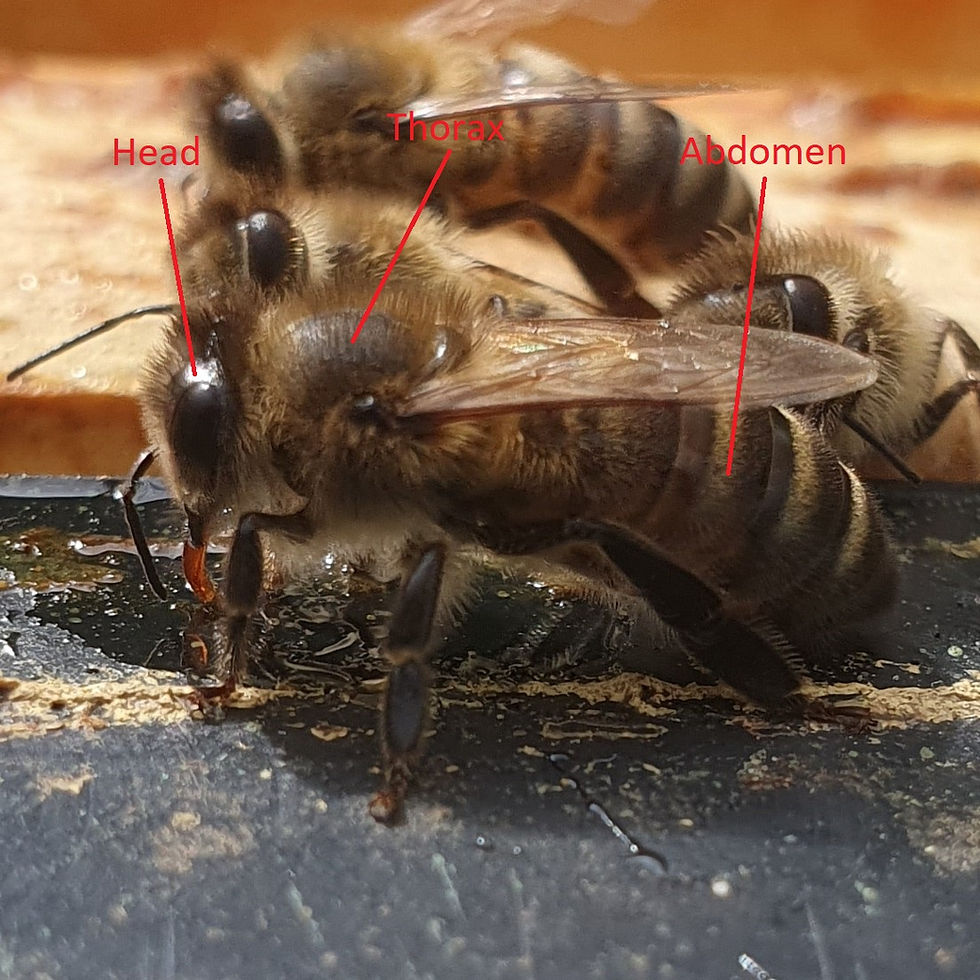

So, this is a honeybee Worker that I’ve named Lucy for the purposes of this blog post. Hello Lucy! We shall be using her to demonstrate the honeybee’s anatomy.

As you can see, she has three main sections to her body, the head, the thorax, and the abdomen. Let’s have a closer look at what each of these sections of the bee brings to the party.

Head

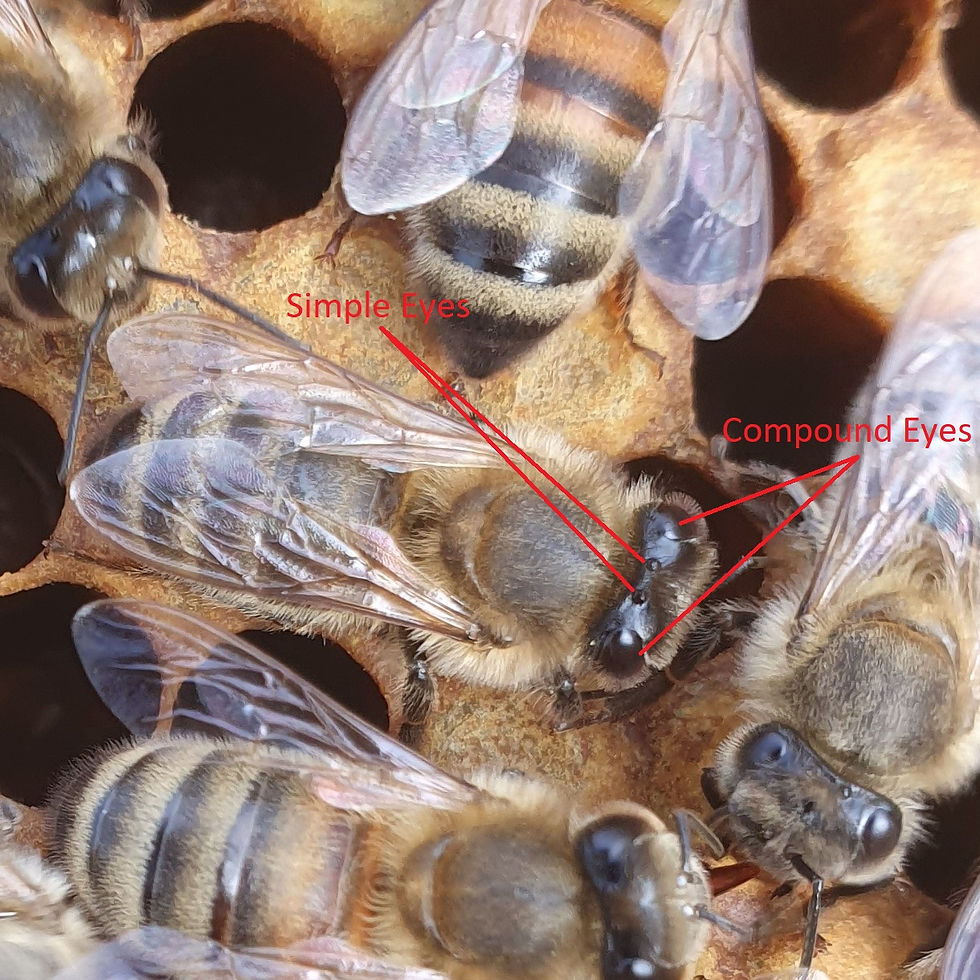

The head contains all of the bee’s sensory organs such as their eyes and antennae as well as other useful tools such as their mandibles and proboscis. The honeybee has exceptional vision thanks to its two sets of eyes. The large black oval things that take up the majority of the bee’s head are the compound eyes. They have multiple sensors which can send individual images to the brain for processing into one large picture. The second set of eyes are named “Simple Eyes”, and these are three, quite hard to distinguish, bumps on top of the bee’s head that collect light from the UV spectrum. When used together the bees can easily distinguish and navigate to flowers, even if hidden by foliage, and can see more colours than our rubbish human eyes.

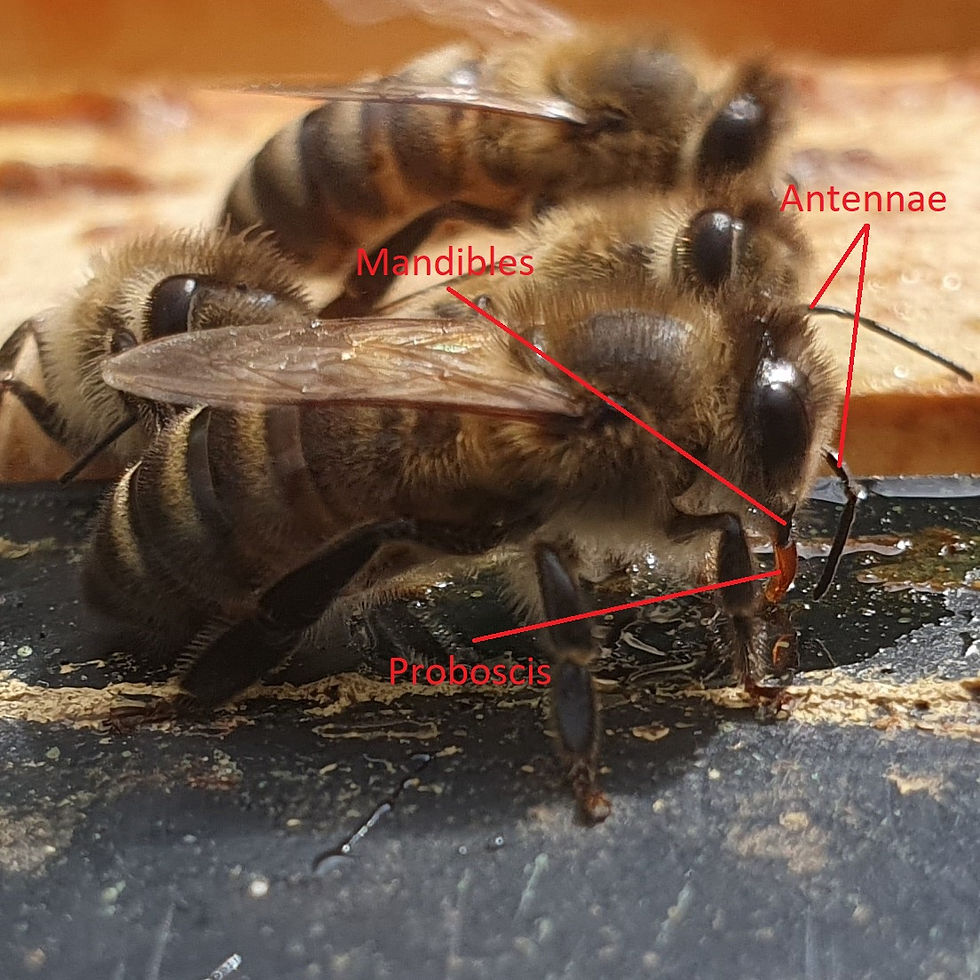

The antennae protrude from the top of a bee’s head and provide a huge range of sensory information such as odours, vibration, CO2, and much more. They are extremely sensitive organs and can sniff out sting pheromones months after the initial sting… to my chagrin…

The jaws (mandibles) of a bee are essentially used as a hand for gripping and manipulating objects. They are extremely strong and grant the bee a lifting strength much greater than its own weight. Another use for the mandibles is to protect the very fragile proboscis. This acts as the bee’s personal straw which it uses to suck up nectar and honey into its body. The cool thing is that the average western honeybee can extend its proboscis by around 6.5mm in length, which considering their whole body is only around 15mm long, its extensive. This allows the bee to effectively collect nectar from some of the deepest flowers.

We’ve talked about the outside of the bee’s head but what about the insides? The honeybee’s brain is about 2mm2 and only has around a million neurons. When comparing this with our own brains that have about 100 billion neurones it seems relatively tiny, but their brains are incredibly efficient and powerful for their size. they can process multiple sets of data and stimuli at the same time, allowing them to make quick decisions through complex reasoning. They also have the ability to store memories of landmarks and directions over miles of flight. What space is left inside the head is taken up by special glands that allow secretions to be produced and released from the mouth. These glands are used for making royal jelly and helping make their wax malleable when building structures.

Thorax

The bee’s thorax is the “middle bit” of the bee, this is the powerhouse of the insect where all of the movement comes from. It is full of the bee’s muscles and if the head is the engine of the bee, the thorax is definitely the motor and wheels.

There are two sets of wings attached to the thorax which allow the honeybee to fly through the air at a whopping 15 miles per hour. A bee’s hind wings are much smaller than its fore wings, but they’re both necessary to fly. To help with lift-off, they slightly twist their wings into a propellor shape for greater aerodynamics. The fore and hind wings then lock together when flying about. Their fast-pulsating muscles create impressive wing-flapping speeds, around 200 flaps a second! This allows their wings to move the same amount of air as a pair of larger slower flapping wings; This means that they can fold back very neatly when the bee is milling about in the hive or on a flower. The bee is able to carry an additional 80% of its own bodyweight while flying, which is an incredible feat of strength.

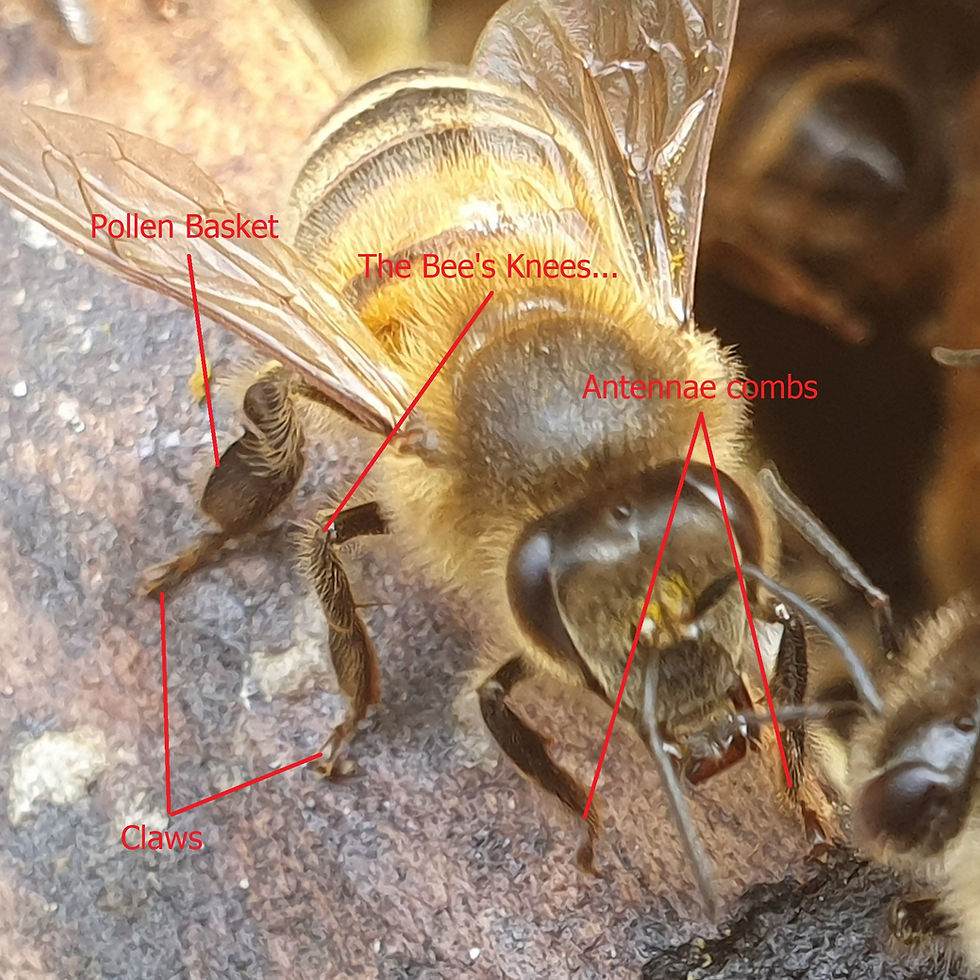

Also attached to the thorax are three pairs of flexible and agile legs. These comes in handy when the insect needs to crawl into awkward places like inside a flower stamen or honeycomb cell... or any gap in my beesuit… In addition to movement, each pair of legs have other jobs which they are specifically designed to do.

A honeybee’s front legs are purpose-built for antennae cleaning, with a handy comb-like tool to run through each antenna. They also have sensitive taste receptors on the bottom of their feet which they use to prod and poke inside honeycomb cells to make sure they’re clean or if the stored honey is ripe enough to be capped.

The Worker bee’s back legs have pollen baskets which are polished cavities surrounded by small strong hairs for storage during foraging missions. They’re able to collect, pack, and carry propolis and pollen back to the hive. The middle and back sets of legs also act as a counterbalance when flying to maintain stability in even the strongest of winds. On the end of all of the bees’ legs are sticky pads and claws to help land and walk on uneven or slippery surfaces.

Abdomen

The abdomen of the bee is kind of like the factory and storage facility of the insect’s body. The abdomen is full of the bee’s important internal organs, such as the digestive tract, “breathing apparatus” (bees don’t have lungs), reproductive organs, wax glands and stinger.

Bees have two stomachs. The first is called the “Honey Crop” and is essentially an expanding sac where nectar and honey are stored to be moved from A to B. A successful forager’s Honey Crop can expand to almost half the abdomen if needed. The second stomach is linked to the first by a special organ called a “Preventriculus” which is in essence a one-way valve, made of muscle and teeth like structures, which prevents food being digested from contaminating the Honey Crop. The second stomach is called the “Ventriculus” or “Midgut”. This is where all the digestion occurs to keep the bee alive. The last part of the digestive tract is the “Rectum” which is pretty similar to the Honey Crop as it can expand to a huge degree. This stops the bees from needing to defecate so much in winter, sometimes being able to cross their little legs for several months at a time.

Bees don’t have lungs… no insects do… It took me far too long to wrap my head around this as I always thought some of the noises that insects made were from voice boxes or something. But yes, bees have no lungs, so this begs the question “how do they breathe?!”

I won’t go into it with too much detail but insects in general have holes down the sides of their bodies called “Spiracles.” Honeybees have three pairs of Spiracles on their Thorax and seven pairs along their abdomen. These Spiracles link to a network of tubes and air sacs called the “Tracheal System.” From here the bee’s blood (known as “Haemolymph”) is enriched with oxygen. The bees refresh the air in their little air sacs by contracting and relaxing their abdomen, similarly to how we use our diaphragm. So, the little butt wiggles they’re doing in this video is them breathing:

Believe it or not, amongst all of these ever expanding and contracting internal organs, the Abdomen also manages to house the honeybee’s reproductive organs. I’ll go into more detail about this in the next section about Castes, but normal Worker bees are all female, and all have female reproductive organs. As the task of reproduction is the Queen’s job and to save space for their Honey Crop, the Worker’s reproductive organs remain underdeveloped. There are times that a Worker will get thoughts above her station and start laying but as they lack an organ called “Spermatheca” the eggs that they lay are all unfertilised.

Something a Worker bee possesses that the Queen doesn’t are glands under the abdomen that secrete four pairs of wax scales. It is released as a liquid that quickly hardens into a texture useful for building out the hive. The bees will collect these flakes and chomp them into a wax ball with their mandibles before placing it somewhere to build a structure. Young Worker bees can produce roughly 16 scales in 24 hours. To put how labour intensive, it is for a colony of bees to draw out honeycomb; 1000 wax scales are needed to make up just one gram of wax! Mental!

I can’t finish talking about the bee’s Abdomen without mentioning the part that everyone attributes to striped insects, the “Sting” AKA “Butt-Dagger.”

A honeybee uses its stinger for defence against other insects and mammals and only as a last resort. Honeybees are usually far too busy to be dealing with anything such as violence when out and about foraging, and the sting impulse only clicks in place when they are near home or feel truly threatened. Interestingly, even though the sting is barbed, the bee often survives stinging another insect as the barbs don’t get caught on an insect’s chitinous shell. Unfortunately, they will usually die after using it on larger animals and humans due to our skin being so elastic and trapping the barbs inside us.

So now that you know the basic anatomy of the honeybee it’s time to talk about the three different castes inside a colony and how to tell them apart.

The Worker

The Worker bee is the most common in the colony. These girls do almost everything in the hive. They babysit the larvae, clean, forage for food, manage the colony, defend the hive, process the nectar into honey, act as air conditioning units and take care of the Queen, plus probably some things I’m forgetting. The Worker bees have far too much to do and not enough mandibles to do it with (think we can all sympathise with that).

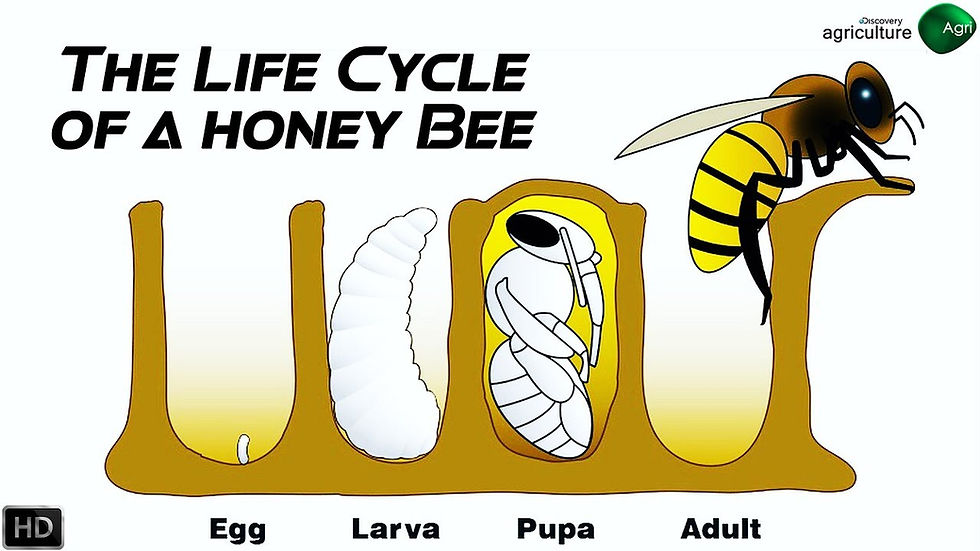

They start their life as a fertilised egg (remember this, it’s important) and hatch after 2 to 3 days. After that, other adult Worker bees feed the larva up for 5 to 8 days, until they virtually fill the bottom of the cell. The cell is then capped with beeswax and the larva wiggles from its C shape to do several somersaults while secreting silken fibres until she is completely covered; at which point she stretches out to the full length of the cell with her head facing the wax cap. This is where the larva, now called a pupa, metamorphosises to an adult Worker bee over 12-ish days.

Worker bees have jobs depending on their age and will slowly stop doing one thing to start doing another as the days go by. The first couple of days the bees clean out cells (starting with their own) ready for the Queen to lay an egg. Between day 3 and day 11 the Workers are feeding the Larvae, the Drones and the Queen. Between day 12 and day 17 the bees are on colony management duty where they move stores about the hive, build comb, cap cells and generally keep the place clean and tidy. At day 18 the bee’s stings have fully matured and they go on guard duty at the entrance for a few days until day 22 when they start flying out of the hive to collect resources. Worker bees live for about 40 to 50 days in total and will spend the rest of their life being gatherers for the hive.

An older Worker bee is still able to do the jobs of its younger siblings, so say there is an accident and only old bees are left. They would still be able to clean cells, feed the larvae and look after the Queen, but they just wouldn’t be as efficient at it. The hive depends on the different ages of Worker bees working together at the same time to make the colony super-efficient, its why the Queen doesn’t really stop laying.

The Drones

We’ve looked at the ladies of the hive, now is the time to have a gander at the males. Drones are quite different looking to workers and the queen, and that is due to their job. Their sole purpose in life is to fly out to find a Virgin Queen from a neighbouring colony and mate with her. The Drone doesn’t do any chores around the hive and in fact they spend most of their time demanding food from the workers when they’re not out looking for a queen. This is because they lack the apparatus to feed themselves, which is a bit embarrassing for the poor lads.

Drones have much bigger eyes than worker bees and the queen (more than twice the size!) as they need to be able to spot a needle in a haystack which is a virgin queen flying about. They are incredibly agile and have much more powerful wings than the other castes as once the Queen has been spotted, they need to catch up with her and accompany her on her nuptial flight whilst vying for position with other Drones.

Unlike the females of the colony, the Drone lacks a stinger and is completely harmless even when in grave danger. Instead of a stinger they have an “appendage” that hides out of sight until mating. These sexual organs are torn from the abdomen after their first use, killing the poor Drone instantly. It’s a hell of a way to go, I guess, especially because the whole process only lasts 5 seconds...

The Drone’s sad existence starts with an unfertilised egg (this is important too). Drone cells are much larger than worker cells as the drone is much bulkier. After a couple of days, the egg dissolves away to leave a small Drone larva in its place. Over the next 10 days the larva is continuously fed by the Worker bees until it is filling the bottom of its cell. Similarly to the Worker larvae, the cell will be capped and the larva with spin itself a silk cocoon to start its metamorphosis. There is a difference between capped Worker brood and Drone other than size. Worker cappings are generally flat whereas drone cappings are domed shaped, like little bullets.

It takes the drone 14 days to metamorphosize completely, at which point it buzzes inside its cell because it lacks the mandibles to cut open the cell’s cap and requires a worker to do it for him. Once free, he unfurls his wings and wanders over to where the food is. He remains here for 6 to 16 days, filling up with nectar and building his fat stores for the flights ahead and further developing in sexual maturity. Once ready he leaves the colony every afternoon between 2pm and 6pm for 20-minute stints at a time, flying back to rest and fill up on nectar before heading out again. Drones can live for 50 days in total, but they obviously are trying their best not to die of old age…

An interesting note is that in a healthy colony Drones are only produced during spring and summer. When the weather gets too cold for them to fly out and mate, the workers physically kick the Drones out of the hive and remove any Drone brood present. This is a survival trait to help conserve food during the winter months. The poor blokes get a really rough deal.

The Queen

The head honcho, the Queen, is the most significant bee in the hive, but you probably already know that. “Queen Bee” is synonymous with the English language (at least) as a term for someone of great import. She alone produces the fertilised eggs that allows Workers to be created to run the colony and she does this with great vigour! The Queen can lay up to 3000 eggs a day when the colony is at peak performance, meaning she can lay more than her body-weight in eggs a day… not quite sure how she does it other than feeding almost constantly. Unlike ants and termites, the queen doesn’t sit still and pop out these eggs. She’s usually marching around the comb finding clean, empty cells to lay a single egg into.

As you may have noticed from the sections before this, the Queen can lay two types of egg, fertilised and unfertilised. All fertilised eggs are female and come from the Queen’s genetics and the “lucky” Drone the sperm came from. All unfertilised eggs are male, and they solely have the Queen’s genetics. Something cool about this is that both Queens and Workers can be produced from the same type of egg, meaning if something happens to the Queen then as long as there are fertilised eggs somewhere in the hive, the Workers can produce another to keep the colony alive. Neat!

“So, what does the Queen have that the other castes don’t?” I hear you wonder.

As the Queen is female, she has a very similar anatomy to that of the worker with a few differences. The Queen’s ovaries are fully developed and are ready to produce vast quantities of eggs 1-2 weeks after emerging from the queen cell. They also have an organ called a “Spermatheca” for collecting sperm from multiple Drones during mating flights. This supply of sperm will allow the Queen to fertilise her eggs throughout her life even though she only goes on one nuptial flight. Due to the size of her reproductive organs, the Queen’s abdomen is much larger than that of a Worker. Her legs are also designed more for grip and feeling out the cleanliness and size of cells before laying.

The Queen has a stinger like a Worker, but it is barbless so she can reuse it again and again without injury. In saying that, the Queen rarely stings and mostly saves it for fighting other Queens (more on that in a later post).

A Queen starts her life as soon as the Worker bees decide they need a new head of the colony. This can be due to a number of factors such as accidental death, disease or swarming to name a few. Once the impulse is switched on in the Worker bee heads, they start finding larva from a fertilised egg, the correct age and size. Once found, the larva is solely fed a special food called “Royal Jelly” for 5-7 days. During this time the larva will grow so big that the cell will need to be elongated by the workers to make sure she’s protected. Interesting to note that Queen Cells always point downwards rather than horizontal to the ground like Worker and Drone cells.

After 7 days the queen cell is capped, and she starts her metamorphosis. This is the quickest change out of the three castes and only takes seven days until she chomps her way out of the cell fully formed. It takes another week for her flight muscles and Spermatheca to mature but then she leaves the hive for her one and only nuptial flight. Multiple Drones will mate with her (and lose their lives) on this flight and then she will return and start laying eggs after only a day or so.

There you have it, a quick summary of the honeybee’s anatomy and their different castes.

If you have any questions about the subjects mentioned in this post, then please contact me via any means and I will answer as best as I can. I will also keep updating these “Beekeeping Basics” posts, so they have any questions received and their answers at the end.

The next "Beekeeping Basics"post will focus on the beehive itself.

I hope you’re all safe and well!

Greg

Anatomy and Castes Q&A’s

Comments